Information Pursuit

an information-theoretic framework for making interpretable predictions.

Background. As deep networks are more readily deployed in taking day-to-day decisons, interpretability of these processes are becoming more and more important. In fact, the European Union now requires by law the “right to an explanation” for decisions made on individuals by algorithms. Initial efforts in this direction majorly focussed on post-hoc interpretability of deep networks. However, post-hoc methods come with little guarantee as to whether the explanations they produce are accurate reflections of how the model makes its predictions. Consequently, in this project we focus on developing a framework for making predictions that is interpretable-by-design.

What is interpretable prediction? Unlike privacy, where notions like differentiable privacy have become central to the development of privacy-preserving AI algorithms, a major challenge in interpretable ML is the lack of a definition for interpretability. This work focuses on interpretability to the user of an AI algorithm, who may not be AI experts themselves. In this context, we argue that interpretability of an ML decision ultimately depends on the end-user and the task. For instance, in image classification problems like bird identification, a model’s predictions are considered interpretable if they can be explained through salient parts of the image whereas in medical imaging, a more detailed explanation in terms of causality and mechanism is desired.

Furthermore, interpretable explanations are often compositional, constructed from a set of elementary units, like words in text or parts of an image. We propose to capture this user-dependent, task-specific and compositional property of explanations via the concept of a query set. Query sets are sets of functions, that are task-specific and interpretable to the user. For example, if the task is bird species identification from images, a potential query set could consist of questions about the presence/absence of different visual attributes of birds like beak shape, feather colour and so on. Given such a query set, how do we make interpretable predictions?

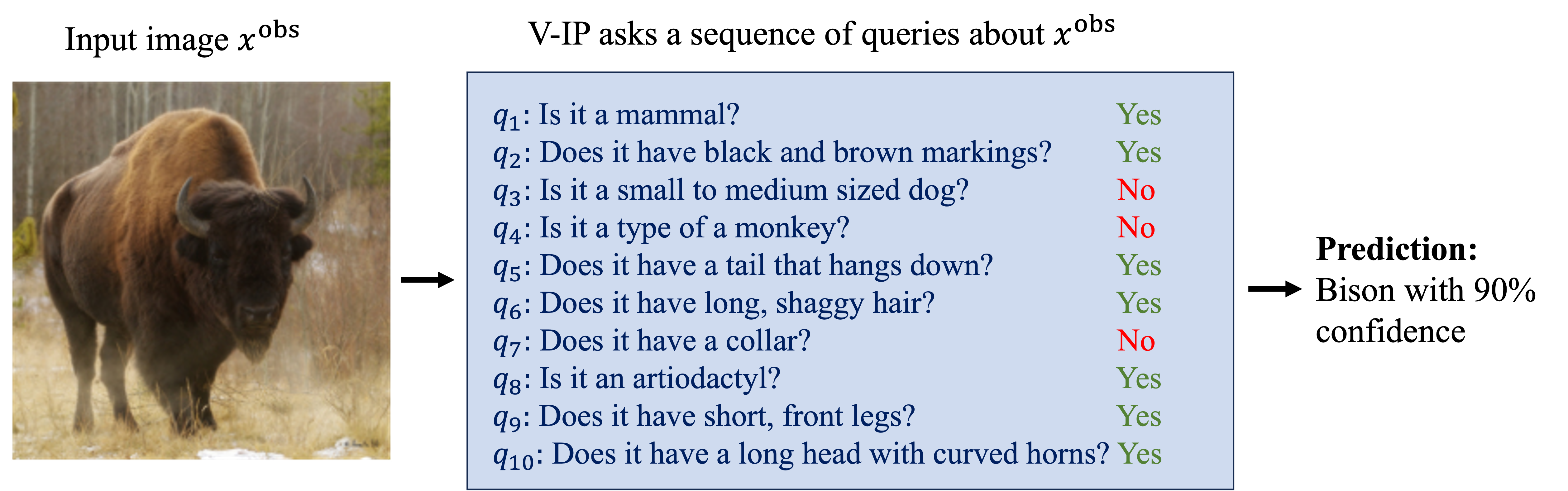

Interpretable predictions by playing 20 questions. Given a query set, we propose to make predictions by playing the popular parlor game, 20 questions. In this game, the ML model sequentially asks queries about the given input (from the query set). Each query choice depends on the query-answers obtained in the sequence so far. Once, the model has obtained enough information from the query-answers a prediction is made. This query-answer chain then becomes an explanation of the prediction that by construction can be interprete by the user. The query answers are either provided by an oracle (input features in data) or by classifiers trained on annotated query-answer datasets. This process is illustrated in the figure below.

In the above figure, the given image is correctly classified as a “Bison” by sequentially asking 10 queries about different characteristics of the image. This query-answer chain serves as an explanation for why the model predicted this image as a Bison. Notice, shorter explanations are easier to read and interpret than longer ones, thus along with making accurate predictions we would like to promote shorter query-answer chains.

Information Pursuit: What query to ask next? Information Pursuit (proposed by Geman & Jedynak, 1996) is a greedy heuristic used in active testing problems where the goal is to select tests (queries in our context) to solve a task (prediction) by carrying out the minimal number of tests on average. IP uses mutual information (MI) between the query answer and the prediction variable to decide which query to select next in the sequence. Unfortunately, computing MI is difficult in high dimensions.

-

In (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022), we propose a generative approach to the algorithm called Generative Information Pursuit, or G-IP. Specifically, we posit a graphical model wherein we assume the query answers to be conditionally independent of each other given the class label Y and some latent variable Z. This conditional independence allows for efficient computation of MI by sampling. The graphical model is learnt from data using Variational Autoencoders and the Unadjusted Langevin algorithm is utilized to carry out inference. Unlike previous approaches, this implementation of IP achieves competitive performance (for the first time) with deep networks (trained by taking all query answers as features) while being interpretable.

-

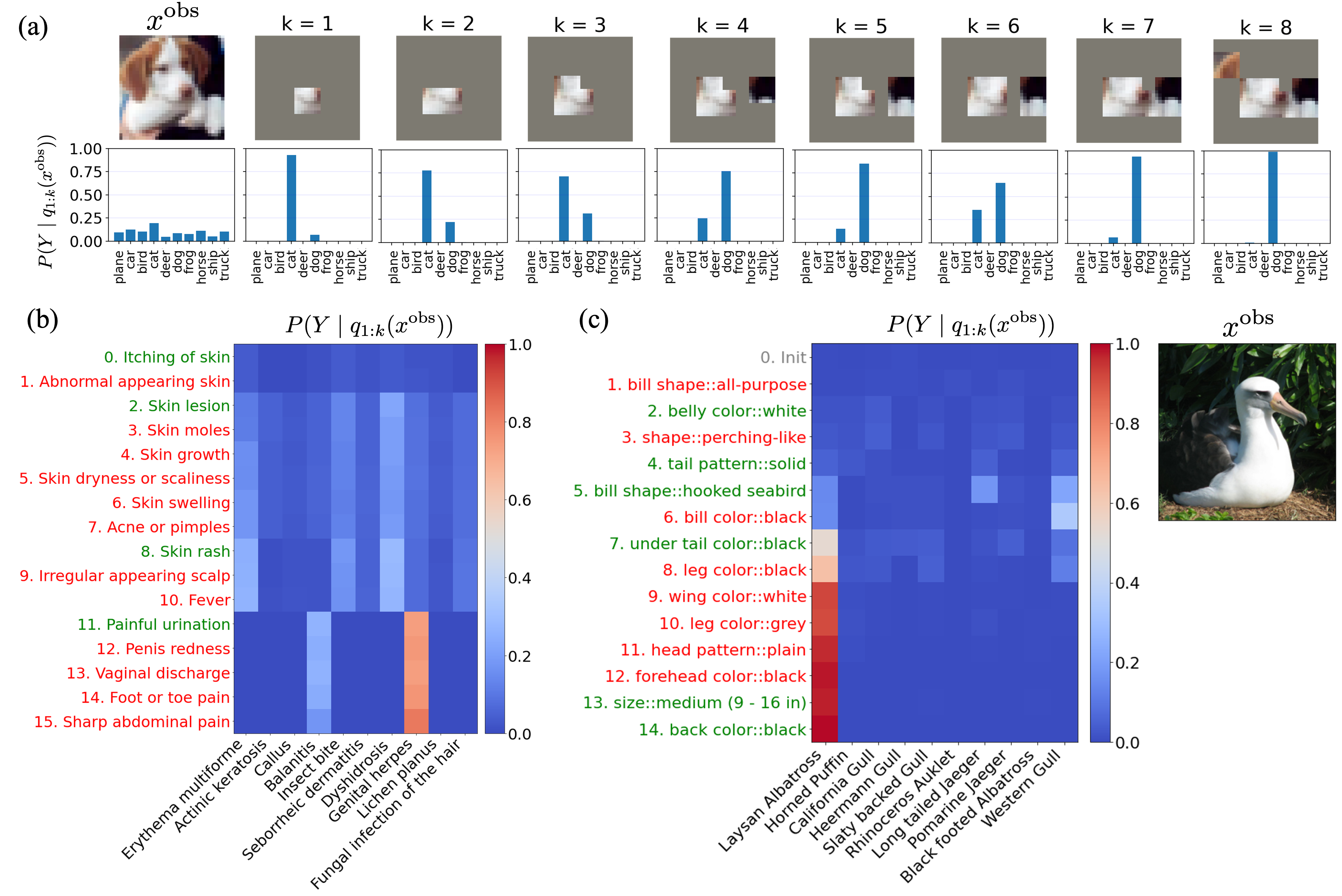

A drawback of the previous approach was that it relied on learning good generative models from that that allow for tractable inference. However, this is a challenging problem in high dimensions. Notice that, we only require a function that learns to choose the most informative next question and not in the explicit value of the mutual information of that query’s answer about the prediction variable. Using this insight, in (Chattopadhyay et al., 2023), we propose a variational characterization of IP, called Variational Information Pursuit (V-IP). This characterization provides us with a non-convex objective that can be efficiently optimized using stochastic gradients and deep networks without the need of a generative model. V-IP allowed extending our framework to large scale datasets like Cifar-100 and SymCAT-300 (a medical diagnosis dataset), where learning tractable generative models is challenging. Code for V-IP can be found here. Below are a few example runs of the V-IP algorithm for different datasets.

Connection with Sparse Coding. In this project, we explore the connections between Information Pursuit (IP) and Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP). Like IP, OMP is a sequential greedy algorithm that is used for sparse coding a given signal in terms of dictionary atoms (columns). In each iteration, OMP selects atoms in order of correlation gain. However, unlike IP, OMP is computationally far more efficient since it only involves vector dot products and matrix projections. In (Chattopadhyay et al., 2023) we prove that OMP is special case of the IP algorithm (upto a normalization factor). Thus, showing, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, that there exists a fundamental connection between these two algorithms that were proposed by two very different communities (the sparse coding community for OMP and the active testing community for IP). Building on this connection, we propose to reformulate the 20Q game in terms of dictionaries of CLIP (a large vision-language model introduced by Radford et al., 2021) embeddings of semantic text concepts and use OMP to sparse-code a given image’s embedding in terms of these text concepts. The result being a computationally simple and competitive classifier (compared to V-IP or G-IP) for making interpretable predictions. Code can be found here.